Soldiers of the Uganda People’s Defence Forces stand in formation. (Photo: US Air Force/Master Sergeant Carlotta Holley)

In an interview with the Africa Center, Stephen Twebaze, a researcher on African parliaments and advisor to the Ugandan legislature, says that when members of parliament see themselves as constituent representatives rather than deployed cadres of their political parties, parliaments can exercise effective oversight even when they are dominated by the governing party. Twebaze has collected, analyzed, and published performance indicators on the Uganda parliament since 1986.

What was the early role of the Uganda parliament in exercising oversight of the executive branch, and the security sector in particular?

During Uganda’s civil war, the National Resistance Movement (NRM) established a network of local committees that governed the areas under its control and held the movement’s commanders to account in cases of misconduct. These committees operated under a National Resistance Council (NRC), the NRM’s legislative body, which continued to operate after it captured power in 1986. It was eventually expanded to 270 members, who brought in diverse perspectives and agendas. Indeed, many new members belonged to the prewar political parties and saw themselves as a check on the nascent government.

The Ugandan Parliament. (Photo: John & Melanie Kotsopoulos)

Although Yoweri Museveni was triple-hatted as Uganda’s President, Speaker, and Defense Minister, even he did not always get his way in the Council’s deliberations. One of the first examples of the Council exercising oversight during the NRM’s formative years in government was the adoption of an expanded code of military conduct for the National Resistance Army (the precursor of the Uganda Peoples Defense Forces or UPDF). Several high-ranking officers were disciplined for misconduct under this code. In 1990, senior police officers were investigated and later prosecuted and jailed for using live ammunition on Makerere University students protesting the government’s termination of support for living expenses, books, and tuition. The Council also established the Office of the Inspector General to independently investigate and seek remedies for abuse of any government office. This body had the power to subpoena, arrest, and prosecute, which it used on several occasions.

The election of 284 independent delegates to the Constituent Assembly, a body of elected officials convened to negotiate and draft Uganda’s 1995 Constitution, marked yet another step in reestablishing parliamentary democracy and establishing independent oversight for the first time in Uganda’s politics.

Some key innovations that were incorporated into the new constitution included clauses establishing civilian oversight of the military, statutes providing for transparency of the intelligence services, and rules establishing several independent institutions. One of these, the Uganda Human Rights Commission, enjoyed wide-ranging powers, such as access to security installations and places of detention without notice to monitor human rights. This has long been considered a model among Commonwealth countries.

What makes for a vibrant parliament, even when it is dominated by a governing party?

The principle of parliamentary supremacy was central to the political ethics and ideology of the NRM during the civil war and in the early years of state consolidation.

Institutional development is an important factor that ensures parliamentary vibrancy even when the governing party remains dominant. Uganda’s Administration of Parliament Act (APA), for instance—one of the few of its kind in Africa—establishes parliament’s complete autonomy in administering itself, setting its budget, and employing its staff. This immediately removed the fear that the executive could starve parliament of funds if it delved too deeply into security matters.

When members of parliament see themselves first and foremost as constituency representatives as opposed to deployed cadres of the governing party, then the body itself can more effectively assert its independence and exercise oversight.

In addition, the cooperation of the executive and its willingness to subject itself to scrutiny can set a new tone and signal a new political trajectory. The executives in Nigeria, Liberia, Namibia, and Sierra Leone all showed strong commitment to parliamentary supremacy during their transitions from war and civil conflict. Sierra Leone’s parliament, for instance, expanded its oversight role considerably since the end of the civil war in 2002, including passing new laws governing the conduct of the National Security Council and monitoring its activities. In Namibia, parliament exercises robust oversight over the Ministry of Defense, as well as the intelligence agency within the president’s office, despite the fact that deputies from the ruling Southwest African People’s Organization (SWAPO) have dominated the body since independence in 1990.

The big takeaway from all this is that when members of parliament see themselves first and foremost as constituency representatives as opposed to deployed cadres of the governing party, then the body itself can more effectively assert its independence and exercise oversight. In Senegal, one would be hard pressed to distinguish ruling party cadres from opposition deputies during plenary and committee debates and parliamentary investigations. Ghana, Tunisia, and South Africa, to name a few, have similar characteristics: Ruling parties in each of these countries hold supermajorities, but parliaments maintain their own corporate and institutional identities that reinforce their independence over and above party lines.

What are some noteworthy achievements in oversight?

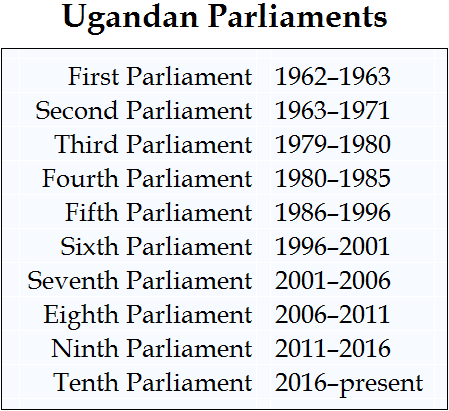

Uganda’s 6th parliament (1996–2001) moved from a plenary-based to committee-based oversight, which allowed it to, for the first time, tackle issues in depth through standing as well as select committees. Thanks to the APA, parliament also had complete control over how it governed itself. The first innovation increased its effectiveness in oversight while the second its independence and autonomy. This, in turn, ensured that parliament could tackle security issues more effectively.

Under the committee system, members routinely summoned ministers to testify, opened hearings to the public, and invited subject matter experts and other stakeholders to weigh in on issues under consideration. Several previously “no-go” topics were subjected to public scrutiny, including the war in northern Uganda, the activities of the intelligence community, Uganda’s military operations, including in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in support of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement during Sudan’s civil war. The establishment of the Public Accounts Committee, which by statutory order is chaired by opposition members, gave parliament the power to audit government expenditures and make them public.

The 6th and 7th (2001–2006) parliaments launched several investigations and initiated police action against culprits. They also applied pressure on other branches of government to launch their own investigations, many of which ran concurrently with parliamentary probes. Subsequently, a commission led by Justice Julia Sebutinde investigated widespread misconduct within the police force, and the Porter Commission—a panel of international, African, and Ugandan judges convened by Justice David Porter—investigated corruption by senior army officers during Uganda’s military operations in Congo. Justice Sebutinde also investigated the military’s purchase of two faulty helicopters from Belarus in a probe that led in part to the sacking of the president’s brother as army chief.

Parliament also looked into corruption and mismanagement in the military, a joint effort of the Defense and Internal Affairs Committee and the Presidential and Foreign Affairs Committee. Furthermore, several “sessional committees” were established to monitor specific ministries, and their findings were then taken up by select committees. By the 7th parliament, 22 sessional and select committees had investigated mismanagement across the Ugandan government, leading to the censure and subsequent firing of several cabinet ministers.

Parliament also looked into corruption and mismanagement in the military, a joint effort of the Defense and Internal Affairs Committee and the Presidential and Foreign Affairs Committee. Furthermore, several “sessional committees” were established to monitor specific ministries, and their findings were then taken up by select committees. By the 7th parliament, 22 sessional and select committees had investigated mismanagement across the Ugandan government, leading to the censure and subsequent firing of several cabinet ministers.

The establishment of the Budget Act further strengthened parliament’s oversight role by requiring the executive to submit preliminary estimates to the parliamentary committees before the budget is presented by the Minister of Finance. Together with the APA, this law protected parliament and enabled it to exert meaningful oversight of the executive branch. Other moves gave parliament control over its security and allowances, provided it with access to classified budgets, and ensured that it was not dependent on ministries and the Attorney General for government information, including the budget and operations of the military, police, and intelligence.

What explains the recent downward trend in parliamentary independence and oversight?

Many executives that once championed reforms and signaled a strong commitment to accountability now view independent institutions as a threat to their hold on power. Patronage and intimidation—and in Uganda’s case, “carrots and sticks”—have been increasingly used to circumvent and weaken these institutions.

During the 6th parliament, lawmakers loyal to the executive strategized to take control of several sessional committees to reduce members’ access to sensitive government information. Army representatives joined the Defense and Internal Affairs Committee and used their numbers to elect a serving general as their chair. Although the committee eventually returned to civilian control after resistance, the trend continued into the 7th and 8th parliaments, where the executive’s lieutenants gained control of other committees such as the Presidential and Foreign Affairs Committee and the Legal and Parliamentary Committee. The latter passed the controversial bill that removed the presidential two-term limit.

The increasing monetization of politics, coupled with the dwindling commitment to ethical principles and ideology, also contributed to a decline in the quality of oversight. Where aspiring lawmakers once ran for office with little more than conviction and their track record, now they sell their properties and secure loans to finance their campaigns. They rarely recover their “investment.” Indeed, it is common today to see Ugandan parliamentarians arrested and jailed for failure to repay loans. As such, the executive has been able to “buy” support from troublesome lawmakers with inducements including cash, cabinet positions, promises of new projects in their constituencies, and access to loans.

Finally the quality of individuals entering parliament has reduced significantly. Experienced and older lawmakers that shaped parliamentary practices from the 6th through 8th parliaments, many of them contemporaries of the president, have been replaced by younger legislators who are less committed to ethical principles and far more susceptible to corrupt inducements. We see similar trends in other national parliaments, including Kenya, Burundi, Tanzania, and South Sudan, as well as in regional bodies such as the East African Legislative Assembly and the Parliamentary Forum of the Southern African Development Community. The Pan African Parliament’s role in expanding accountability and oversight has been miniscule.

What lessons can other legislatures learn from the Ugandan experience?

First, without parliamentary independence and autonomy there can be no effective oversight. Ugandan legislators learned early on that constitutional stipulations were not enough. Enforceable statutes also had to be established if parliament was to build its own capacity outside the executive. Second, autonomy meant that parliament had to have full control of its budget, as well as its day to day administration. Third, institutional independence demanded the establishment of a research and investigative service, budget office, and legal counsel, answerable only to parliament. This ensured that the body could function on its own, without relying on the other branches of government for data, investigative capabilities, and legal assistance. Fourth, public participation through hearings, investigations, and a popular parliamentary internship program, increased the citizens’ trust in the legislature. This enhanced parliament’s duty to exercise oversight on citizens’ behalf.

Without parliamentary independence and autonomy there can be no effective oversight.

The negative trends in Uganda’s parliamentary practice are mainly due to a decline in the willingness of lawmakers to exercise oversight and assert their independence as a result of a sharp increase in patronage stemming from efforts by the government to hold onto office. Parliament’s institutional and legal architectures, however, remain intact and its capacity has continued to increase. Uganda’s experience therefore debunks the assumption that the quality and effectiveness of oversight necessarily improves due to an increase in institutional capacity. The attitudes, willingness, and convictions of lawmakers play at least as important a role in the effective functioning of parliament. Along with this, the need for parliament to develop its own corporate and institutional identity separate from the executive is also key.

The blandishments of the executive through inducements is not sustainable in the long run given the sheer size of parliament and the ever-shifting alliances among lawmakers. While the quality in oversight of the 9th and 10th parliaments pales in comparison to the 6th, 7th, and 8th, rebellions by ruling party lawmakers unwilling to toe the party line have become commonplace. This is leading to a new dynamic that could reintroduce vibrancy in the future.

Additional Resources

- Africa Center for Strategic Studies, “Scrapping Presidential Age Limits Sets Uganda on a Course of Instability,” Spotlight, August 27, 2018.

- Paul Nantulya, “Different Recipes, One Dish: Evading Term Limits in Africa,” Africa Center for Strategic Studies, Spotlight, July 28, 2016

- Uganda Journalists Resource Center, “Dataset: Parliamentary Performance over the Years,” Blog, June 26, 2016.

- Christopher Clapham, “From Liberation Movement to Government: Past Legacies and the Challenge of Transition in Africa,” Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, January 2013.

- Nelson Kasfir and Stephen Hippo Twebaze, “The Rise and Ebb of Uganda’s No Party Parliament,” in Joel Barkan (ed.) Legislative Power in Emerging African Democracies, Lynne Reinner Publishers, 2009.

- Nelson Kasfir and Stephen Hippo Twebaze, “In Name Only: Uganda’s Constituency Development Fund,” in Mark Baskin, Michael L. Mezey, Distributive Politics in Developing Countries: Almost Pork, Lexington Books, 2004.

More on: Security Sector Governance Military Professionalism Uganda